Erik Wiitala: An Immigrant's Story (Part Four)

The life of my Finnish American great-grandfather

The fourth in a six-part series documenting the life of my great-grandfather Erik Wiitala, who left behind a childhood of poverty in Finland to travel to Michigan’s Copper Country, initially working in the mining town of Red Jacket before homesteading in Misery Bay. In Part Four, Erik remarries following the tragic death of his first wife. As his family once again begins to grow, so does the surrounding area. A look at the businesses, schools, churches and social halls that sprung up in this decidedly Finnish American community.

Back in Erik’s home village of Alavus, there’d been a young girl he’d teasingly referred to as his “little wife.” Her name was Eliina Mäkinen, and she’d had a crush on him, had respected him. She was 16 when Erik left Finland, and now here it was 13 years later, Erik newly widowed, starting out on a homestead with five young children, making inquiries as to her situation. She had a nephew living in Red Jacket who was able to inform him that she was unmarried, working in Helsinki as a nanny in the home of a doctor. Erik wrote to her, but what did that letter say? He likely laid it all out on the table, sprinkled with a little sugar, as it could take two months to receive a reply to a letter sent so far away.

Might she be interested in joining him in the States? He certainly sparked her curiosity, as she accepted his offer to travel to the Copper Country to check things out. He helped pay her fare, but after arriving at Ellis Island she hesitated. He wrote to her again, this time to New York, asking for her hand in marriage. In October of 1902, less than two years after his first wife died, Erik was remarried.

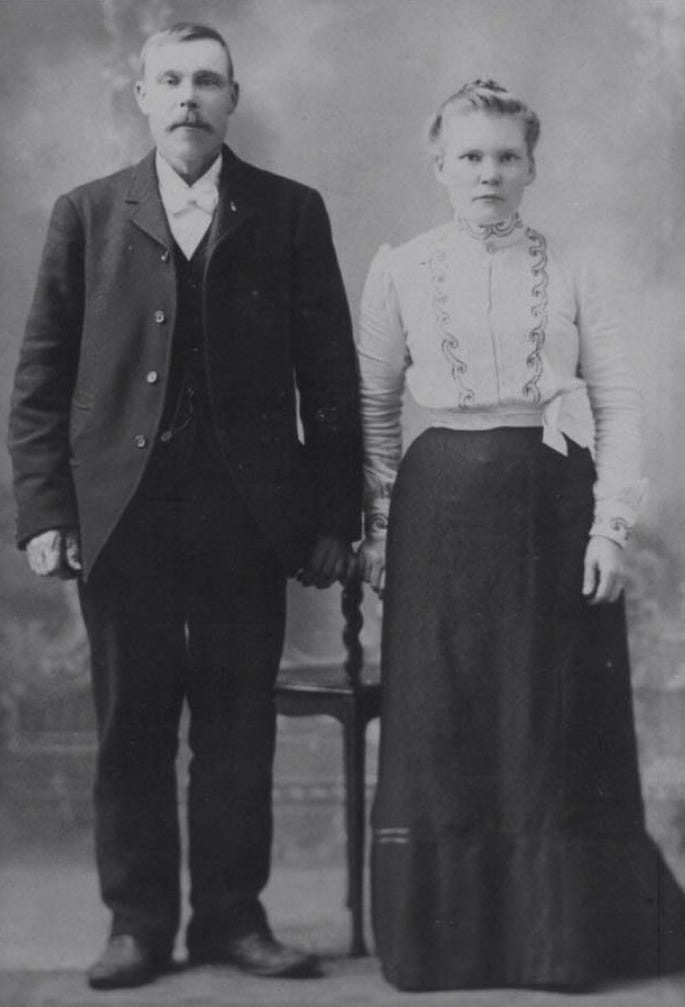

In their wedding portrait they stand side by side, each with a hand on a small, decorative table between them, their pinky fingers touching. Erik wears his one and only plain suit with a white shirt and bow tie. His sandy blond hair is neatly combed and he’s grown a mustache. He looks pleased enough with the situation, but it’s hard to tell what’s going on in Eliina’s mind, given her impassive face. She wears an intricate white blouse and a long dark skirt. Her very blonde hair is braided and wound up in a bun. She was a stereotypical Finnish beauty with prominent high cheekbones; a small, slightly upturned nose; and almond-shaped, pale blue eyes that hinted of stubborn strength. Like Erik, she spoke fluent Finnish and Swedish, and was said to have a beautiful singing voice. She was also a devout Lutheran, a purveyor of the hellfire and damnation-type preaching that made parishioners wail and burst into tears. Erik wasn’t the least bit religious, but his first wife had been, and so he was used to being married into it.

I wonder if Eliina felt like an outsider among her neighbors initially, so many of them being relatives of Erik’s first wife. So many feelings could have come into play, but clearly she was needed. I doubt her step-children would have dared to sass or disobey her; Erik wouldn’t have tolerated it. And soon more children began to arrive; Eliina would have eight in all, five boys and three girls: Harold, Wilho, Lauri, Waino and Eino; and Miriam, Helmi and Jenni. At some point a second story was added to the house, providing two bedrooms upstairs, one for the boys and one for the girls.

Ever since homestead rights first became available in the area in the early 1890s, others had also made their way into the woods of Toivola-Misery Bay, most arriving by land rather than boat. With a wagonload of supplies, they carefully picked their way through the forest, bypassing swamps and steep hills and portaging across swollen streams. It wasn’t long before the first crude roads appeared, neighbors working together with some help from logging companies. Most were just two-track cow paths that cut right through private land, so if someone expanded a pasture well beyond the road, gates were put in for passing through.

The soil was heavy with clay that when waterlogged, caused wheels to sink, creating deep ruts. After a heavy rain, the hills became so slippery, they were often impassable. The earliest cars went up on blocks from late fall until things dried up in the spring, and side roads wouldn’t see a snow plow for many years to come. Most switched to sleighs, with a four-horse team occasionally coming through pulling a roller that helped compress the snow for easier travel.

The main trunkline would be the Misery Bay Road, starting at the highway in the community of Toivola and dead ending in Misery Bay. Toivola had started out as a lumber camp, but as more and more people arrived, so did a train station, a post office, and several stores. It was a jaunt for the Wiitala family to travel the nine miles to get there, Erik and several of the kids leaving home after morning chores, the horse pulling the wagon so slowly over the rough roads, it was sometimes preferable to just walk alongside. At the store, each child was given a nickel to buy an ice cream cone while Erik loaded up the groceries and other necessities. He’d buy lunch as well, crackers and a ring of bologna that they’d divide up, washing it down with soda pop.

The largest of the stores was Lahikainen’s, eventually a co-operative owned by the very people who shopped there. Produce was bought from the farmers at a fair price and merchandise mostly bought wholesale, the savings passed onto customers through lower prices. Any profits were put back into the business, reflecting the socialist tendencies of the early Finnish Americans.

Lahikainen’s store boasted the first telephone in the area, while also offering a weekly grocery delivery service for a fee. Until the post office was established in 1905, this was where the mail got dropped off, and anyone could take it from there with the intent to deliver it to others, though sometimes a few days (or weeks) late. Once the postal service contracted a mailman, the post was delivered by a team of pintos pulling a canvas covered wagon or sleigh along the length of the Misery Bay Road. At each intersection a cluster of mailboxes represented the outlying farms. For some, this still meant a trek of several miles to fetch the mail.

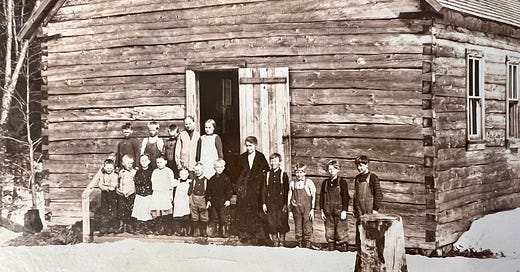

Other signs of a community being established included the building of schools, churches, and social halls. Four different grade schools would serve the Toivola-Misery Bay area, including the one the Wiitala children attended, aptly named the Misery Bay School. The initial structure was a log building donated by homesteader Paavo Marsi, Erik’s father-in-law. According to my grandma, when she started at this school in 1917, there were 64 children enrolled with just one teacher. That teacher taught all subjects to eight different grade levels, with many of the beginning students speaking very little English - it was Finnish that was spoken in the homes. Now throw in meager supplies, living in the middle of nowhere, sometimes having to light the woodstove and shovel the steps - it was all more than enough incentive to find a job elsewhere. Early on most teachers lasted a year. In the 1920s, a proper one-room schoolhouse was built on land donated by homesteader Taneli Marsi, Erik’s brother-in-law. That building is still in use today as a community hall.

There were two churches, one serving the Apostolic Lutherans and the other the Evangelical Lutherans. Prior to this, certain homesteads hosted bible studies, hymn sings, and a traveling pastor who performed baptisms and weddings. Early baptismal certificates bore the name of Urhola as the place of birth, meaning “Place of Heroes.” This was what the pastor considered those who dared to carve a living out of so isolated a place. That name didn’t stick, however; Toivola did, meaning “Place of Hope.” Land was also donated for an official cemetery, superseding at least one smaller, earlier attempt found on Old Rink Road, where several infants were laid to rest, their wooden markers bearing the family name followed by “peipi”…baby.

Two community halls were built within sight of one another. The Toivola People’s Hall was primarily a dancehall but also hosted plays, concerts, and meetings, and could be rented out by clubs and for parties. The other was the temperance hall, officially known as the Toivolan Soihtu or Torch, where the more pious could meet for similar purposes, minus the dancing and while abstaining from alcohol. Some called the dancehall Remula Halli, or “noisy hall,” presumably from the loud music that often poured out late into the night. Eventually struck by lightning, it burned to the ground, with certain people claiming it God’s will.

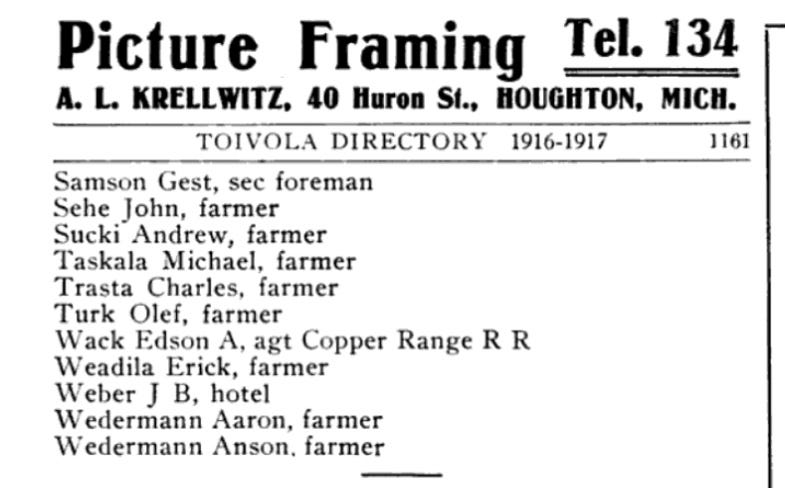

In 1916, a directory was published for the Copper Country, with listings by location and residents by last name, address, phone number and profession. My great-grandfather Erik was listed as a farmer in Toivola, his last name misspelled “Weidila.” He didn’t have a phone number though; telephone lines wouldn’t reach Misery Bay until the 1960s. Another of my great-grandfathers, Anselm Wiideman, was listed as a farmer in Toivola by the name of Anson Wedermann. It seems whoever was put to the task of compiling the area’s inhabitants had little experience with Finnish names, and I would have loved to witness the collection of that data.

But let’s head into Part Five by backing up to 1905, a significant year for the Wiitala homestead…

Read Part Five here.

Or Part One here.