Erik Wiitala: An Immigrant's Story (Part Five)

The life of my Finnish American great-grandfather

The fifth in a six-part series documenting the life of my great-grandfather Erik Wiitala, who left behind a childhood of poverty in Finland to travel to Michigan’s Copper Country, initially working in the mining town of Red Jacket before homesteading in the Finnish American farming hamlet of Misery Bay. In Part Five, the United States government officially grants Erik his 160 acres of land. What that certificate represented, as well as a more detailed look at the Wiitala homestead and the activities that dominated a small-scale dairy farm.

In a photo taken around 1905, a group of men are gathered in the woods, some sitting, others standing, eating their lunch off of tin plates while working at Morrison’s lumber camp in Toivola. Most wear a flannel shirt, work pants with suspenders, work boots, and a cloth hat of some sort. Among these men are three of my great-grandfathers: Erik Wiitala, Anselm Wiideman, and Kalle Heikkinen.

Winter through early spring was a more idle time on the farms, and with property taxes to pay, logging offered farmers a much-needed source of income. Sunday was the men’s only day off, with the decision to journey home dependent on the weather and distance. Often they were away from their families for several weeks at a time.

On the 20th of March of 1905, while Erik was likely still at camp, the United States government officially granted him the patent to his 160 acres in Michigan’s Bohemia Township. Less than two months later my grandpa Wilho was born. Arriving premature, he was so small and delicate that Erik, who assisted his wife in the delivery, feared touching him with his large, rough hands. Wilho would thrive though, and later that year a journey by train to Red Jacket was in order, the booming mine town where streetcars and an opera house were among added features since Erik had removed his family to Misery Bay five years prior.

Now they were just visitors stopping in at a portrait studio where Erik, wearing his one and only suit, sat for the photo, holding baby Wilho in a long, white christening gown. Standing with one hand on his father’s knee and looking wary of the photographer was two-year-old Harold, outfitted in what appears to be a dress, common enough for little boys of that era. Erik’s wife, Eliina, stands with one hand on the back of Erik’s chair, her face, as always, expressionless. Erik though - he looks so proud, so pleased, this man who started out as a beggar boy on the streets of Alavus.

If he were a braggart, if you could read his thoughts, if I were to exaggerate…

We’ve got a nice 160 acre dairy farm going that I now own, situated in a charming little Finnish American settlement on the shores of Lake Superior, a place every bit as beautiful as Finland. Did I mention I’m a land baron? And do you see my cute, fertile, fastidious, hard-working wife? And these healthy young boys who are now landed gentry?

A gentleman farmer at 40 years old, having been in the United States for 17 years. It hadn’t been easy; it hadn’t been without a great deal of work and even some tragedy, but now here he was, an independent land owner. It was living the dream - the Finnish peasant’s dream anyway.

Back in Finland it’d taken land and land alone to become wealthy; a nice profit could be made through the leasing out of small parcels for others to farm. But that wasn’t the case in the United States, and so those who helped establish the many Finnish American farming communities in the Copper Country would largely remain subsistence farmers, growing enough food for their own family and livestock, while generating a small amount of income from the sale of cream. Yet supporting themselves in this way, being one’s own boss, toiling in the fresh air at a familiar form of labor was preferable to what might be had back in the mine towns. And occasionally, other opportunities came along. During World War I, for instance, the government paid farmers including Erik to take up the raising of sheep to alleviate a wool shortage. During the Great Depression, the Ford Motor Company paid to log his 130 acres of wooded land, shipping the timber to a sawmill in Pequaming where among other things, it was used to make boxes for Woody pickup trucks. Other farmers in the area took to raising potatoes, a crop that grew well enough in the rocky, clay-rich soil, and just as important, stored well in the time it took to get to market.

To see the Wiitala homestead at its peak would have been to visit in the 1920s. Though still considered poor by those with jobs in the city, there was now enough money to provide for a few novelties, such as hobby animals. By damming a small creek that ran beside the house, Erik created a narrow pond, adorning it with a bridge and two large swans. The water was only about six feet deep, but the kids still enjoyed poling around on a raft up until the day one of the infants fell in and that was that, Erik destroyed the dam and sold the swans.

Visitors were greeted by a tall archway over a gated entry to the driveway, beyond which was a scattering of buildings. Five of these were interconnected for ease of access in wintertime: a horse barn, two cow barns, a heinälato or hay barn, and a woodshed. There was also an aitta for storing grain, a sheep barn, and a small playhouse for the children. Some of these structures were made of logs, others from boards. Some were windowless, while others had a single window. Some had roofs comprised of horizontal planks, while others had planks set vertical to the ridge. All had lofts for storage. Curiously, there was no sauna on the property - the family simply used that of their neighboring relatives. A sauna was a fire risk and took a great deal of wood to heat, so sharing them was far more efficient and fulfilled a secondary purpose: sauna days were for socializing. Treats were brought along to share at coffee table afterward, the adults catching up on news and gossip while the children played with their cousins.

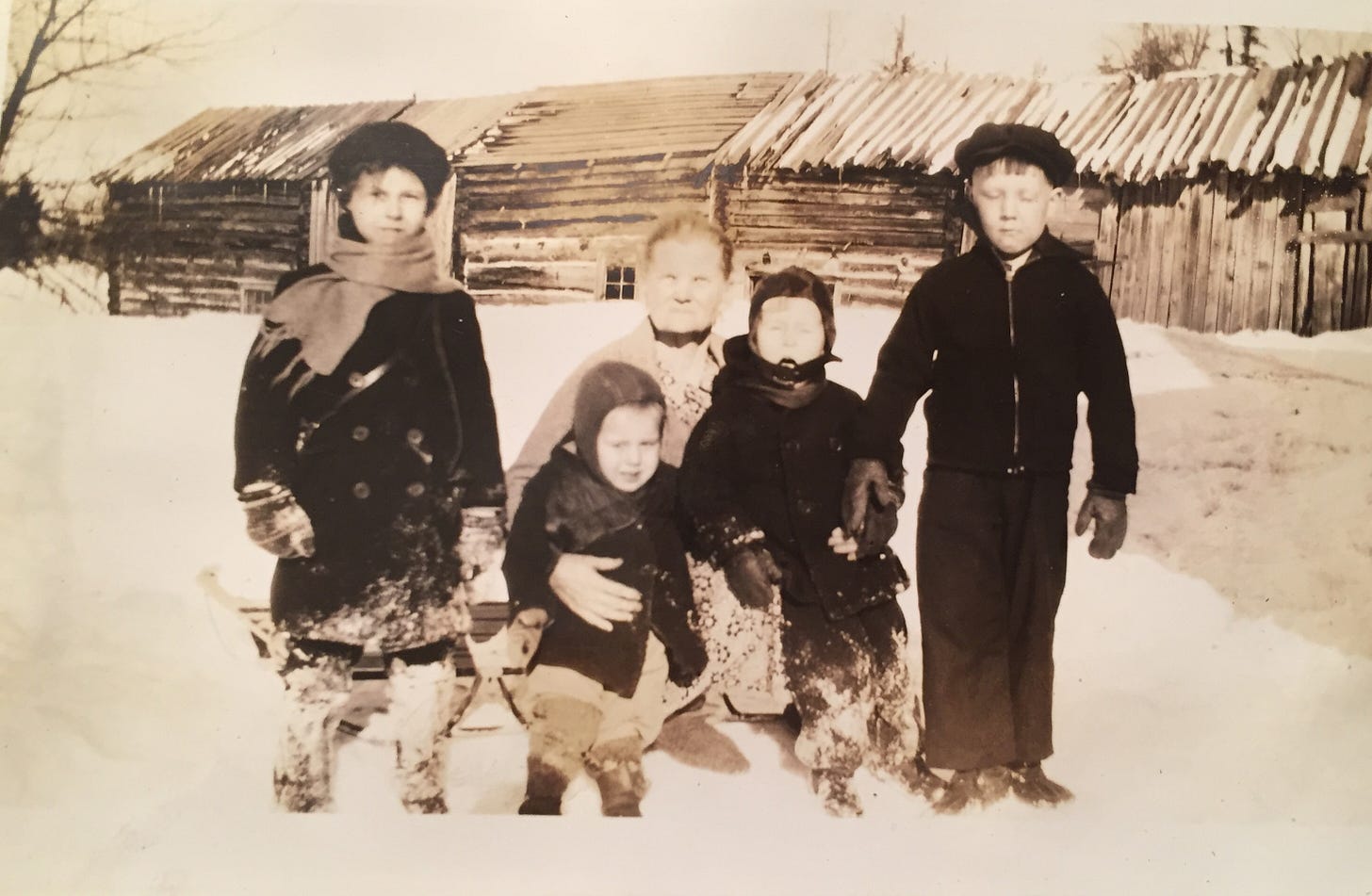

It was common for homesteading families to be photographed in the farmyard with the house in the background. Often the horses were included too. All of these things - the land, the house, the horses - these were signs of prosperity, and such photos often made their way back to relatives in Finland along with some cash. Look Ma, I made it! In one such photo, Eliina and her five youngest children stand in front of the house. As was their tendency for humor, the dog sits alongside on a kitchen chair. Eliina has her hands on the shoulders of blonde little Jenni, who’d go by the nickname of Jingo. On one side of the house a pantry has been added off the kitchen, and on the other side a two-story exterior shed contains the stairs to the second floor. A ladder leads to the roof in case of a chimney fire, though what you can’t see is that the bottommost rungs have been removed to keep Jingo from climbing up there again. A small flower garden grows against the house, a swing sits in the side yard, and a fence surrounds it all. Fences kept the cows out.

Next to no one kept a large herd, with five to ten cows being typical, and unlike today’s large-scale dairy farms with their massive black and white Holsteins, most of the cows back on the Misery Bay farms were brown Jerseys or mixed breeds, far smaller in size. They also had horns. Farms today prevent them from emerging by burning off the early buds, so most people don’t realize that female cattle naturally have them.

Every morning and evening they were milked by hand, each producing about a gallon a day. The cream was removed by centrifugal force using a hand-cranked separator. Butter might be churned as well, and early on, both had to be hauled by wagon over rough roads to the highway in Toivola, where they could be traded at one of the stores for staples like coffee and sugar. As road conditions improved, the cream, placed inside large metal canisters, was wheeled to the roadside for one of the commercial dairies to pick up, earning the farm a paycheck. The leftover skimmed milk was consumed by the family and fed to any calves or pigs.

In order to keep producing milk, cows needed to regularly calve, and that necessitated a bull. Bulls were moody, expensive to feed, and only served the one purpose, so not many farmers kept them; those that did charged a stud fee. As for the resulting calves, females were future dairy cows, while males were either sold to a cattle buyer or butchered and eaten by the family, something some farm kids never quite got used to.

During the long winters the cows were housed in the barn, so come spring, once the farmyard had dried up a bit and the grass had started to sprout, it was scene of pure joy as they were let back out, leaping about and kicking up their hooves. Most Misery Bay farmers didn’t pasture them; they were left to freely roam the roadsides and old logging trails, sometimes travelling for miles to graze on whatever they could find. Hence the fences to keep them out of yards. Every herd had a boss cow, one that naturally ran the show and wore a loud bell that clunked as the others followed her wherever she chose to go. Being that the bells were homemade, each farm’s had a unique sound that announced the return of the herd for the evening milking, though sometimes their clock was off and the children had to be sent out to fetch them.

Through the long winters the cows were largely fed a diet of hay, with haymaking taking place in July, Heinakuu on the Finnish calendar, literally meaning “hay month.” Before mechanized mowers came along, the cutting was done by men swinging scythes, a physically demanding job. During both threshing and haying season, neighbors helped neighbors, the women preparing enormous meals served several times a day to the hungry work crews. After it’d had some time to dry, everyone helped rake the hay into piles, sleeves rolled up, dressed in light-colored clothing under the hot summer sun. From here it was pitched into a wagon, the men scrutinizing the load for balance - they piled it to enormous heights. Back at the barn, an upper wall was removed and a pulley system used to hoist it into the loft. This was where the children played and slept that night, serving as compressors to make room for the next day’s load. The cows had feed for the winter ahead and for the rest of their lives, the smell of a freshly cut hayfield would instantly transport many a former farm kid back to fond childhood memories…

Read Part Six here.

Return to Part One here.