Erik Wiitala: An Immigrant's Story (Part One)

The life of my Finnish American great-grandfather

This series originally published in the Finnish American Reporter.

There comes a time when those who could answer the questions are gone - there is no longer someone to ask.

Each of us derives from eight great-grandparents. Trace the generations further back and it quickly becomes staggering, the number of couples that united, long enough anyway, to result in your being here now. How much love and despair, worry and work, laughter and pain, struggle and hate, celebration and joy? How many stories worth telling, but never recorded? Even the mundane of our ancestors’ everyday lives would be fascinating to us now, yet what we’re often left with is a piecing together, researching dates from legal documents and archival records, merging what memories the old-timers retain with what scraps of writing survive, with photos no one bothered to label, filling in gaps with educated guesses of what was most likely.

During a roughly 50-year period starting around year 1870, over 350,000 people left Finland for North America, a mass migration triggered by poverty as well religious and political oppression. It was time to take a chance elsewhere. The majority came to the Lake Superior region, where the men found work in lumber camps, for the railroads, and in the mines and mine towns. Soon though, many grew restless with this way of life as well, turning instead to farming, an occupation they were familiar with, most having come from rural villages. All of this was true for Erik Wiitala, my great-grandfather and the central character in this story.

Born in 1863 in the Vaasa municipality of Southwestern Finland, Erik was a child of the poorest of peasants and just three years old when a devastating famine spread throughout the countryside. As a young boy he wandered from farm to farm near his home village of Alavus, seeking charity and to work in exchange for food and if he was lucky, some money. He was a beggar boy. As he grew older he travelled further from home, all the way to the Baltic Sea that separated Finland from Sweden, gaining experience along the way as a farmhand, fisherman and woodworker. He and his older brother, Tuomas, would send money back to support their parents and five younger sisters. So many girls had been a string of bad luck; they stood less chance of finding work and were paid less.

At the time there was a practice in Finland known as huutolaisuus, in essence an early form of social welfare whereby children whose parents couldn’t afford to care for them were brought to public auction. The lowest bidder was paid the sum of their bid by the local government and in exchange, the bidder agreed to provide food and shelter for the child at that price per annum. These children were expected to earn their keep through their labor, but not every situation was abusive, and they often ate better this way. Nonetheless a family’s pride was at stake, so when Erik and Tuomas learned one of their sisters had been auctioned in their absence, they gathered the necessary funds to allow their mother, now a widow, to buy the girl back. It was the final push Erik needed to leave for America, where he’d heard there was good money to be made.

In 1888, at the age of 24, he left Finland. His name, however, has yet to be found on any passenger lists. One relative would claim he’d been a stowaway - an exciting story, but Erik was said to be an honest man. Another claimed he worked his way across, trading his labor for passage. Whatever the means, he most likely traveled first to Sweden, then to a port in England, possibly Hull. From here a train crossed the country to Liverpool, where most ships bound for America departed. During an interview in 1942, he recounted how he slept among boxes, barrels, horses and other cargo, and found himself among a group of men having to protect the single Finnish women from roving members of the ship’s crew.

Rather than complete his journey via train after arrival to Canada, he instead found further passage along the future St. Lawrence Seaway, ultimately arriving in Hancock, Michigan, via the Portage Lake. How long was his journey? How did this man who spoke Finnish and some Swedish, but no English, communicate his itinerary? Impossible to know, yet he’d made it to the Keweenaw Peninsula, what the Finns called kuparisaari, the copper island.

Hancock at the time was an expanding community dependent on a single industry: the mining of copper. A steady stream of traffic flowed daily between the docks and the nearby train station at the base of Tezcuco Street. Stores, hotels, and saloons sat perched along the steep hillside, while way above stood the Quincy Mine, lifeblood to it all.

This place he’d arrived to, what would come to be known as the Copper Country, was a melting pot at the time. Over 30 different nationalities were in residence, immigrants lured by the promise of work. Surely his ear would have caught familiar words being spoken among the strangers he encountered. By that time even a number of businesses in town were run by Finns, including a general store, a saloon, and of course numerous public saunas. But Erik wasn’t at his final destination yet, that was further north to the village of Red Jacket (now known as Calumet), where he knew some men from Alavus. The train cost money - the fare from Hancock via the Mineral Range Railroad was fifty cents in 1876, about $13 today. Walking was free, so that’s what Erik did, four miles to what is now the village of Dollar Bay and then up the hill for another ten.

Red Jacket was home to another wildly successful mine, the Calumet and Hecla, where men drilled deep and narrow tunnels following the path of the copper deposits. Few native-born Americans were willing to risk their lives ten hours a day, six days a week doing the dirty and dangerous work of mining. The solution to a labor shortage came from abroad, and one of the primary recruits were the Finns. Notorious for their work ethic, once set to a task they doggedly continued until it was done, sometimes to the point it appeared foolish to others. Perfect! All in all the copper mines of the Keweenaw would employ Finns more than any other ethnic group. Few of them, however, attained the actual title of “miner.” Those men came from places like Germany, Austria, and Cornwall, England; bringing with them the knowledge to determine where the richest concentrations of copper lay, drilling the holes into the surrounding rock, and setting explosives to blast it all free. Mining wasn’t an industry back in Finland, and so the Finns were mostly employed as trammers: they loaded the jagged, dense, blasted rock into rail cars by hand before pushing those cars down dark, narrow tunnels to a waiting skip where it was pulled to the surface. Tramming was a job that relied on physical strength and that exceptional work ethic.

Like many Finnish men, Erik was an excellent woodworker, able to craft anything from furniture, to skis, to a log home. Not only was he a skilled fisherman, he could also build the boat and make the nets. He knew how to plant and yield crops from the poorest of soils, and how to raise and care for farm animals without the luxury of a veterinarian. But these weren’t skills sought after in Red Jacket, and so determined to stay out of the mine, he built a small sailboat and became a commercial fisherman, taking up residence in a rustic shack along the shoreline of Lake Superior in an area known as Calumet Waterworks. It was here that a Finnish family by the name of Marsi, walking along the beach one day, struck up a conversation with him. Within a year Erik would marry one of the daughters, Maria Marsi.

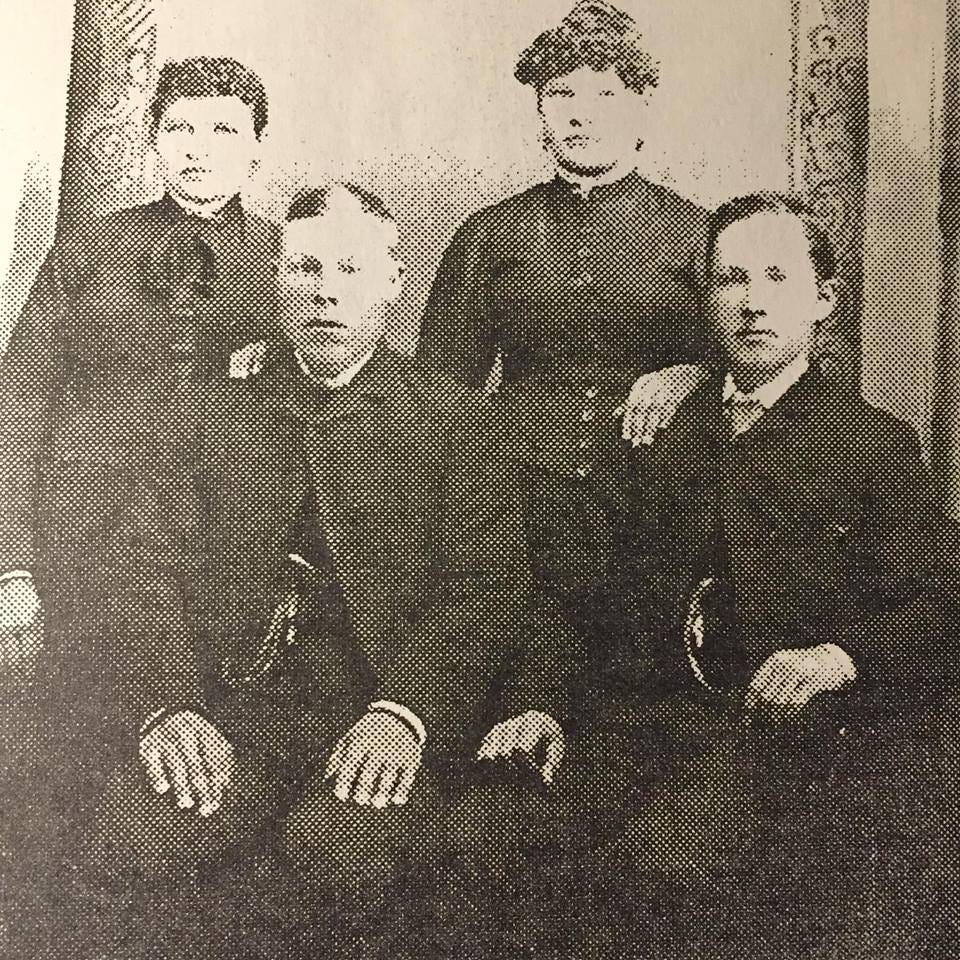

A studio portrait is the only known image of Maria to carry down. She stands behind and to the side of Erik, one hand resting on his shoulder. Her nose and mouth are dainty, her cheekbones characteristically high. Short, dark curls frame her fair-skinned face, a face that is expressionless. She wears what was likely her best blouse and a long skirt. Maria’s sister, Katri, and her husband, Antti Lindgren, strike a similar pose to the right. The men are dressed in suits, each with just the top button of the coat closed, watch chains dangling prominently from inner vest pockets.

The couple moved into a house on Pine Street, Petäjäkatu as it was called in the mostly Finnish neighborhood. Erik continued to fish while Maria looked after the boarders they took in. She’d prove to be a good worker, about the highest compliment you could pay a Finn. She’d also be pregnant more often than not over the next several years with little time to rest: up early to start the fires, draw water, make breakfast, and pack the lunch pails for the men. Then cleaning, more cooking, and laundry done by hand, all while caring for her children.

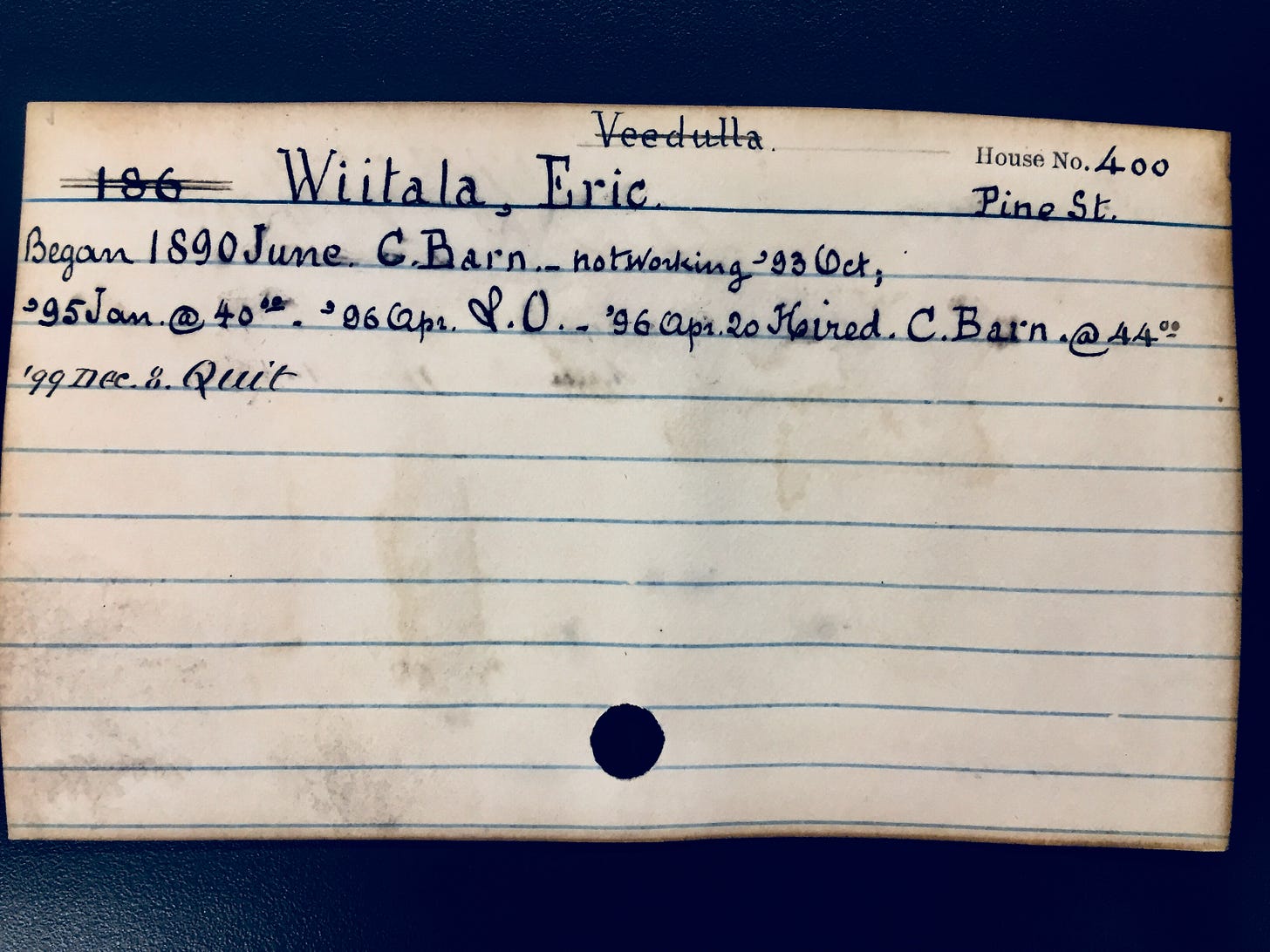

Their first child, a girl they named Katri, died in infancy. Maria was soon pregnant again, at which point Erik finally took work at the mine. However, in keeping with his determination to stay above ground, he reported to the “Barn,” the complex at the Calumet and Hecla where men were assigned a wide variety of labor-intensive tasks. He’d be paid less than the men who went “below,” but likely considered this a fair trade-off.

On his employment card found in the Michigan Tech University Archive, his name is written in large, fine script, while above it is written “Veedula,” perhaps serving as a pronunciation guide for the mining office’s staff - Finnish surnames were a mystery to most. There’d be people who’d suggest he change his name to something familiar like Erikson, but no, his father had been Juho, not Erik, and he wasn’t Swedish. He’d make one small change to the spelling though, replacing the letter V with a W - what had been Viitala became Wiitala. It made no difference in how the Finns pronounced it, but to non-Finns he was thereafter Erik “Weedula.”

Daughter Anna was born in 1891, Erik serving as the midwife. He’d assist in the births of all but one of his 15 children. Another year passed, bringing along son Juho, who died soon after birth and was buried alongside Katri. There was nothing extraordinary in their deaths; the rate of infant mortality was simply high back then. Another year later and a healthy son, Edvard, was born in August of 1893. Two months after that, Erik was laid off from work. The United States had entered an economic depression temporarily reducing operations at the mine. It would prove to be a pivotal event in my family’s history, providing an opportunity to look into a different way of life, one far away from the noise and congestion of the copper cities…

This six-part series is free and available to everyone. Read Part Two here.

Edit: Soon after making this post, a man messaged me from Alavus, Finland (Erik’s home village). In seeing the photo of Erik and his first wife, Maria, he immediately recognized their faces. It turns out he had a photo of them, one that belonged to a neighbor living not far from the original Viitala farm. Now I can say that I have a clear image of Maria, one that made its way to Finland long ago, and now back to the States and to me. This is why I am writing - to find connection - and as I said in another post, sometimes astonishing discoveries happen along the way, what feels as though my ancestors are reaching out from beyond the grave, saying “remember me.” This photo qualifies as astonishing.

This six-part series is free and available to everyone. Read Part Two here.

Your details are so well written and I really appreciate your work on this topic! Erik is one of my great grandparents too and I’m trying to gather information of my Finnish family tree with so many branches!!🤗🇫🇮

Heart warming. As I sit here in Trimountain/South Range...