Erik Wiitala: An Immigrant's Story (Part Two)

The life of my Finnish American great-grandfather

The second in a six-part series documenting the life of my great-grandfather Erik Wiitala, who left behind a childhood of poverty in Finland to travel to Michigan’s Copper Country, initially working in the mining town of Red Jacket before homesteading in the Finnish American farming hamlet of Misery Bay. In Part Two, Erik takes advantage of a temporary layoff from the Calumet and Hecla Mine in order to look into a different way of life far from the copper cities.

Tired of making shareholders in some distant city rich, Erik and his in-laws craved a more independent and meaningful life, one tied closely to nature. Through the Federal Homestead Act of 1862, tracts of forested land could be had from the United States government for what was initially about $18 in filing fees. Equivalent to about $600 today, this land wasn’t free, but it was cheap. The rules stipulated that a home had to be built on the property and lived in for five consecutive years, with at least five acres of land cleared for farming.

While laid off in 1893 from the Calumet and Hecla, Erik and six other men set off in his sailboat, skirting down the western shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula, looking to check out surveyed land made available near the village of Ontonagon. Included in the party was Erik’s father-in-law, Paavo Marsi, and his two brothers-in-law, Antti Lindgren and Taneli Marsi.

Short of their destination a storm blew in, forcing them to take shelter on a crescent-shaped, white sand beach bordered by high dunes. This was Misery Bay. They decided to venture into the nearby woods to see what suitable land might be available here, and what they found was virgin timber with a canopy so thick, very little grew in the shade below. The tall white pine trees were especially valuable, these would be used to build their homes. The land was also relatively flat with creeks running through - an added water source. There was no need to travel any further, and they soon returned with the government surveyor, each man staking a claim of 160 acres and in doing so, taking his place among the founding fathers of the future farming community that would take its name from the bay.

Misery Bay - sounds like a nice place. One can’t help but wonder as to the origin of such a name for so beautiful a stretch of Lake Superior shoreline. Once people began to ask, the oldest citizens couldn’t achieve a consensus. Perhaps a band of Native Americans once lived along the shore with a similar sounding name, as remnants of an Indian village and burial grounds were apparent at the mouth of the Misery River. Or maybe a group of early white settlers were forced to vacate the area after a particularly harsh winter, having faced starvation and freezing. Or was it because of the miserable roads early on, the clay slick and deeply furrowed, often impassable. What misery! Better to just walk the shoreline - the Sand Road as some called it - before cutting back into the woods to get to one’s destination.

One thing was clear: in daring to venture out like this, to move to a place so remote, not yet accessible by roads, they’d rely heavily on sisu, a trait defined in a variety of ways. It’s the ability to persevere beyond reason, an alarming tenacity of purpose, a tendency to bite off more than one can chew and then chew it. It’s how the Finns survived centuries of scraping by in their homeland. They’d also need a tremendous amount of know-how, both the men and women. If something stopped working for instance, if something broke, you couldn’t just bring it elsewhere to have it looked at. You had to understand how it worked and figure out a way to fix it yourself.

Moving into the wilderness with the intent of carving out a farm also required a deep knowledge of the forest, the soil, the weather, and the plants and animals - both wild and domestic. It helped that the climate was similar to Finland, with the same distinct seasonal changes, the same shifting in daylight throughout the calendar year. Winters were long, cold, dark and snowy; the summers mild with 16 hours of daylight at the solstice - a day they celebrated known as Juhannus. The landscape was also familiar, the forest interspersed with swamps and bogs, rivers and streams, small inland lakes and one lake so large, it reminded them of the sea. But the belief that Finns came to this region because it reminded them of their homeland is a fallacy; they came for work and work alone, and while for some there was comfort in the familiar geography, for others it made them homesick.

The usual late fall storms preceded Lake Superior’s freezing over, the men returning to Misery Bay in the spring of 1894, the women and children staying behind in Red Jacket. They began clearing the land, leaving stumps in place for the time being, to be burned or dug up once there was a draft horse to help pull the roots free. They constructed mostly temporary shacks, but atop a hill overlooking the creek on Taneli’s property, one much finer structure was built. Comprised of a single room measuring 13 foot square, it would serve as a shelter from rain, a place to eat and sleep, and as a savusauna - a smoke sauna.

First the surrounding earth was leveled and packed down, then rocks added upon which the logs would sit. Those logs were marked along their lengths so as to be straight and the proper width before a broadax was used to hew their sides flat. Any remaining bark was peeled off before the ends were carefully notched to interlock tightly where they’d meet at the corners. The next tier was scribed to match any idiosyncrasies in the logs below, minimizing gaps, while wooden dowels placed along the lengths further locked the layers together. It would’ve taken about a day to complete a single tier, with nine bringing the walls to a proper height. This was heavy and exacting work and they proceeded carefully. If someone were to get hurt, if a log slipped or there was a careless swing of an axe, the nearest hospital was far up the shore or through the woods. There wasn’t room for error.

The roof of the sauna, comprised of rafters and joists, was covered with cedar shingles nailed atop rough, hand-sawn planks. More planks formed the gable ends, with a hole cut near the top of a gable to act as a flue. Along with a door there was a hatch, a räppänä built into one of the walls that could be opened for ventilation and light.

Inside, a few boards were likely laid upon the dirt floor leading to a raised bench, with a ladder providing access to the loft space above. Rather than a stove, relatively flat rocks were stacked in a corner without the use of mortar, creating a chamber known as a kiuas in which the fire was built. With no chimney, smoke would quickly fill the room, billowing from the flue near the roof but also leaking through any small gaps in the walls. Seeing this from the outside, anyone unfamiliar with the practice would have thought the building was on fire. It took several hours for the space to reach a desirable bathing temperature - the Finns liked it hot - at which point the fire was allowed to die down, the flue plugged, and water splashed upon the rocks. The resulting steam helped clear any lingering smoke, and over time the walls and benches became lacquered with black soot, though some say it never transferred to the skin.

You have to imagine it, the men sitting atop the bench in the dim light of a kerosene lantern, the scents of maple and birch smoke, pine sap and cedar intermingling. With hushed voices they reflect on the day and discuss plans for the next, but mostly they sit with their private thoughts; they were a laconic people after all. With sweat beading on their bodies in the hot dry air, a dipper of water is thrown on the hot rocks, generating steam, löyly, taking the breath away momentarily, increasing perspiration. With a switch, a vasta made of cedar branches, they’d swat at their tired muscles, massaging them and stimulating the skin - thought to improve circulation. No scrubbing with soap - stepping outside, a rinse with warm water was followed by an invigorating bucket of cold dumped over the head. Refreshed and relaxed, the heat would radiate from their skin for some time after.

The economic depression in the United States continued through 1894, so whether by choice or lack of work, Erik remained absent from the Calumet and Hecla Mine until January of 1895, a 15-month hiatus. Once again employed at the Calumet barn, his wage was $40 a month, some of which was sent back to family in Finland. Daughter Sanni was born in March, and in April there was another brief layoff during which it appears someone had a word with management, as Erik’s wage increased to $44 a month, a 10% raise.

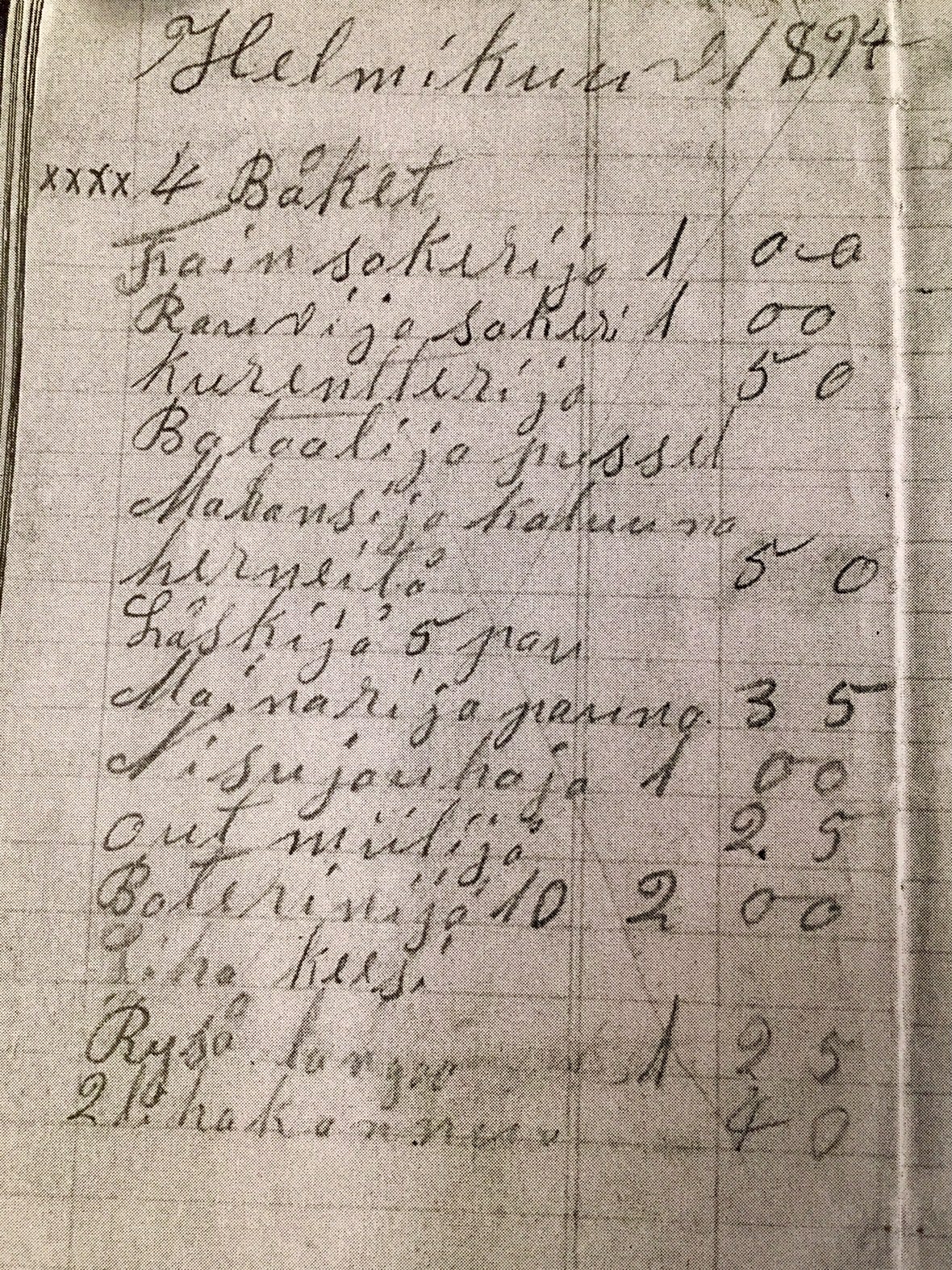

What he and his wife Maria earned from the boarders they took in is hard to say, perhaps it only covered their own room and board. Erik kept a ledger in which he recorded certain expenses. Despite having been direly poor as a child, sent out to work at a young age, he could read and write. Children in Finland were generally literate, though not necessarily taught at school. They learned through confirmation classes at the local church or on farms after the day’s chores were done. It was an important part of the culture, but penmanship was mostly self-taught, and so only the most diligent managed to achieve the script seen in Erik’s ledger. On its pages he mostly recorded store-bought expenses, some of the words in “Finglish,’ staples bought in bulk including coffee, dried peas, sugar and flour. There was kerosene for the lamps and fabric for sewing clothes, but for a few months certain new items appeared, including tar and nails. Erik had begun building a new, much larger sailboat.

Two more years passed with son Otto arriving in April of 1897, making for a family of six: Erik and Maria along with daughters Anna and Sanni, and sons Edvard and Otto. Having dragged his feet as long as he dared, Erik finally filed an official claim for his land with the United States government. To this point he’d put faith in the honor system, but rumors of claim jumpers, of others filing for land someone else had staked and begun to clear, spurred him to take action. Now he had to abide by the rules of the Homestead Act, which included the five-year timeline.

In January of 1899, daughter Ida was born, and that December Erik’s employee card indicated he’d quit. His in-laws had also been wrapping up their affairs. With the start of a new century the time had come to move their families to Misery Bay, where life would be primitive for years to come, a life in which they could anticipate working even harder than in town, the women working even harder than the men. I wonder how Maria felt about it all. One of their sons was certainly apprehensive, as three-year-old Otto went missing on moving day. Eventually found hiding under a bed, he feared leaving Red Jacket, having heard stories of wolves and bears lurking in the deep woods, waiting to tear him limb from limb…

Read Part Three here.

Read Part One here.

This is rich with so much interesting information about life back then! Erik sure had Sisu, and his wife had to find hers as well!! I loved reading this!😉👍🏼