Erik Wiitala: An Immigrant's Story (Part Three)

The life of my Finnish American great-grandfather

The third in a six-part series documenting the life of my great-grandfather Erik Wiitala, who left behind a childhood of poverty in Finland to travel to Michigan’s Copper Country, initially working in the mining town of Red Jacket before settling in the Finnish American farming hamlet of Misery Bay. In Part Three, a look at what homesteading required, from supplies and livestock, to know-how and courage – sometimes in the wake of tragedy.

In the summer of 1900, and 12 years since he’d arrived in the United States, the time had come for Erik to move his young family from the bustling mine town of Red Jacket to their new home deep in the remote woods of Misery Bay. It was 30 or so miles of sailing down the western side of the Keweenaw Peninsula. Care had to be taken at Rockhouse Point, where a shelf of red sandstone jutted out well from shore, the water deceptively shallow, but safely past this hazard Erik slipped the boat into the bay. Landing at the mouth of the Misery River, the children and supplies were lifted out and the boat hauled a short ways up the river where it was tied to a tree. A two mile walk through the woods brought them to the homestead, where a house comprised of just two rooms awaited them: a kitchen and a living room, both doubling as bedrooms. The interior walls were bare logs, no wallpaper or plaster, the floors rough-hewn planks. Each room did have three windows, an extravagance that made the spaces brighter and somewhat less confining. The loft space above was mostly used for storage.

Beyond borrowing from the hartipänkki, a “Finglish” term referring to the bank of one’s heart, what was the cost to start out on a homestead? One historian estimated $1000, approaching $37,000 today, an unlikely sum for Erik and his wife Maria to have saved up. A number of items they already owned, including bed linens, lamps and lanterns, cookware, and by all means a coffee grinder. A cast-iron, wood-fired cook stove was a necessary major investment, but certain things, a plow for instance, would have been shared initially among the four related neighbors on Misery Bay’s future South Road. Along with Erik and his wife Maria and their five children, there was Maria’s bachelor brother, Taneli, who lived right next door. Maria’s sister, Katri, lived across from Taneli with her husband Antti and their four children. A short ways down in the opposite direction was the fourth homestead, owned by Paavo and Anna Marsi, parents to Maria and her two siblings. Cooperation among these four parties would be one of their most powerful tools.

Homemade items saved money. The women spun raw wool into yarn that they used to knit hats, socks, scarves and mittens. As skilled seamstresses, they worked without patterns and often reinvented garments altogether, passing them down from one child to the next. Meanwhile with his woodworking skills, Erik crafted everything from wagon wheels, to skis, to the kitchen sink. He’d also make shoes for the family from homemade leather, using various-sized wooden forms he’d carve.

Food was bought in bulk: large sacks of salt, sugar, dried peas and coffee beans; hundred pound bags of flour; boxes of dried prunes and raisins. In the garden they’d plant beets, carrots, turnips and potatoes, all of which stored well in the cellar. Eventually, many of the farms would have expansive fruit tree orchards that included pears and plums, though apples remained the standard. It was a custom in Finland to plant a tree at the birth of a child, and so Erik would for each of those that came along in Misery Bay.

Berries must be mentioned too; they were nature’s candy. Back in Finland there’d been wild bilberries, lingonberries and cloudberries. In the forests of northern Michigan, the women and children and sometimes the men picked raspberries in July, blueberries in August, and blackberries in September. Other nationalities, especially those living in towns, considered this foraging uncivilized.

Today, no “good” Finnish American passes a ripe berry bush without stopping to pick, but back in the homestead days it was a big job. Into the woods they’d go, all day, day after day, sometimes walking many miles to find the best blueberry patches. Lunch was eaten picnic-style, served with coffee brewed over a campfire. Back home, the berries were sorted, washed, mixed with sugar, and boiled on the stove, perfuming the kitchen with fruity fragrance. Hundreds of quarts of sauce and jam might be preserved during a good year, to be enjoyed throughout the following winter.

As for meat, Misery Bay was teeming with abundant wild game: partridge, white-tailed deer, and snowshoe hare. Speckled and brook trout could be caught in the streams, and herring, lake trout, whitefish, and salmon in the big lake. Though bag limits had been imposed in Michigan by this time, families living in the middle of nowhere harvested what they needed. Storing fresh meat in winter was a matter of hanging it from the rafters of an unheated outbuilding, but in warmer weather it had to be canned, salted, or cured with smoke in the sauna. There was no refrigeration; if something was to be kept cool it went inside a crock in the cellar, into a root cellar or nearby creek, or down the well.

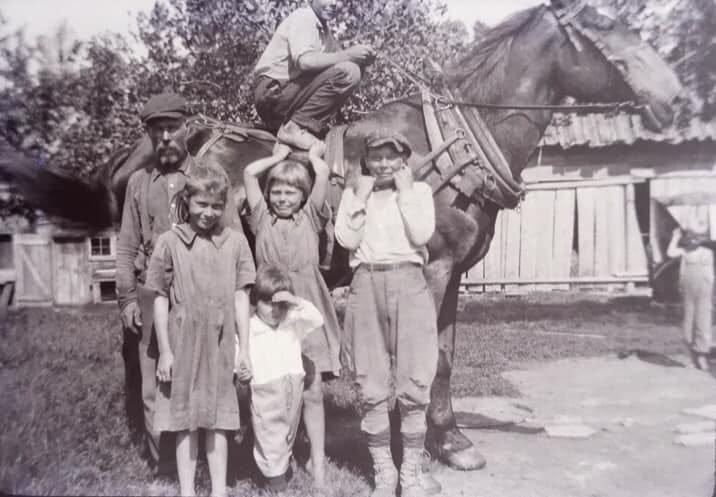

They kept chickens for eggs, and each family started out with one or two cows. Getting fields established and crops planted required a tall, muscular draft horse. A young horse could cost over $200, but lumber camps often sold work-weary beasts at a reduced price, $80 or perhaps even less if there was some noticeable, off-putting affliction. They’d perk up quickly however, given some rest, pampering, and time to graze in the sunshine. These horses were patient, gentle giants that easily operated by command, and the Wiitala homestead would own one or two at any given time with names like King, Chubby, and Roy. King cost next to nothing, arriving thin, inattentive, and with a serious cough, having spent over 20 years hauling logs in the winter woods. Under Erik’s expert guidance he was soon restored to health, and pound for pound worked every bit as hard as his master in the pulling of plows, mowers, hay rakes, wagons and sleighs.

In the remote woods there’d be no fire department, police or doctor within easy reach. The list of illnesses that plagued and often killed people before modern medicine was long: polio, measles, mumps, small pox, diphtheria, tetanus, tuberculosis, typhoid, whooping cough, puerperal fever. Antibiotics and vaccines were a thing of the future, but living in the sparsely populated woods, breathing fresh Lake Superior air, there was less likelihood of being exposed to anything contagious. A limited number of medicines were relied upon: liniments, peroxide, balsam of myrrh, whiskey. Home remedies as well, such as pine tar for respiratory complaints and colds, and pine pitch for cuts, burns, and sores. Some still believed in the hocus-pocus of the old country, “wisdom” handed down over many generations, some of it remnants of an ancient pagan belief system, largely ineffective if not entirely contraindicated.

Then there was sauna. Sauna on köyhän apteekki. Sauna was the poor man’s pharmacy, good for relaxing strained, tired muscles, and easing the ache of rheumatism and arthritis - common afflictions among the hard working. Just the simple act of cleansing one’s body could provide a sense of control in the midst of uncertainty. For the flu, whiskey was the thing, up to a quart (a quart!), slowly sipped while sweating in the sauna, then straight to bed if you could still make it there. For others, a smaller dose with sugar in a mug of hot water had a similar effect.

Throughout that first summer and fall in Misery Bay, the men continued felling trees, putting up fences, tending the livestock, and making firewood and hay. Until there was an established hay field, Erik cut a fair amount of fodder from around ponds and swamps and along river banks. It took strength, skill, and agility to work on uneven terrain, taking care to avoid stumps and rocks that would dull the scythe - maintaining a sharp blade was a source of pride.

With a large apron to protect her clothes, Maria would have been busy cooking, baking, canning produce, tending a garden and the livestock, and serving as seamstress, governess, nurse, laundress, and maid. Finnish women were noted for the cleanliness of their homes as if it were a competition, regularly scrubbing the floors on hands and knees with a stiff-bristled brush and soapy water. Hauling water from the well was a never ending task: water for cooking, cleaning, laundry, and washing up. Doing the laundry was an all-day operation that left hands worn raw from the harsh lye soap. Of course the children helped when not getting underfoot; all but the baby did chores.

Certainly life wasn’t devoid of joy, but that first autumn, did they manage to pause and appreciate the astonishing fall colors? You couldn’t find a prettier blend, the yellow birch and poplar mixed with the brilliant red and orange of maples, then throw in the dark green of pine and hemlock. But as with the woodland creatures, there would have been an earnest rush to wrap things up before the snow, and a lot of snow due to a phenomenon known as lake effect. With little warning it could start to fall so fast, a whiteout was possible in under a minute, the strong winds causing drifting that sometimes necessitated an exit from a window to shovel out the door. The sun might not be seen for days, only to suddenly break free of the clouds for a few precious minutes before being obliterated again. Instead of keeping paths shoveled to the various outbuildings, it was far easier to place poles in the snow to mark the routes and just keep packing it down by foot, creating hogback paths. Narrow and rounded as the name implies, accidentally stepping too far to either side meant being swallowed up in several feet of snow.

Winter evenings were long, with over 15 hours of darkness at the solstice. Men might whittle with a carving knife, a puukko, while sitting beside the warm stove, and when the women finally sat down they’d take up their mending or knitting with hands that often crippled over time with arthritis, from wear and tear. Maria, however, wouldn’t see it come to this. Mid-way through that first winter in Misery Bay she suffered a strangulated hernia, a sudden tear in the abdominal wall. The pain would have been severe and without treatment, soon accompanied by fever, nausea, and necrosis. It was an emergency situation requiring surgery, but she refused to try reaching a hospital, what would have been an excruciating, long, and uncertain journey given the time of year. She died in her own bed in a matter of days.

Why Erik and three other men, most likely his in-laws, then risked their lives to bring her body to Red Jacket is a mystery. Perhaps the thought of her lying frozen in an outbuilding until spring was too much to bear. They set out by sleigh with three horses, traveling through the deep snow along the frozen lakeshore. It took them three days, Erik later saying that the whiskey they brought along helped quench the men’s thirst. Surely it also fueled their bravery and numbed their sorrow. Come spring, as was her wish, Maria was buried alongside Katri and Juho, her two babies lost in infancy.

Following her mother’s death, Anna, the eldest child in the family, became mistress of the house and surrogate mother to her four younger siblings, ranging in age from two to seven. She was just ten years old herself, traumatized and grieving, yet she had a job to do. The household limped along, the neighbors helping as much as they could, but there was no way around it - Erik needed to find another wife and soon…

Read Part Four here.

Read Part One here.

I am marveling at the story you’re telling! What a life of hard work and determination…and such heartache for Erik and his children!!🥹